Unit 2: Leadership of Digital Learning Programs

Managing Change

While the current model of schooling is “often (inaccurately) referred to as the factory model”, the roots of American education as we know it today are more aligned to Horace Mann in the mid-19th century. Mann argued that universal public education should transform American children into “disciplined, judicious republican citizens”. His model was based on the Prussian model of education, and while it mimics a factory based on modern understanding, the factory was not the driver of this model.

A system so engrained in American society, in which every person has participated in their formative years, is a difficult system to change (“I went to school and didn’t need these things, so why do we need to do it now?”). Many education reform efforts fail for this reason. In 1958, President Eisenhower signed the National Defense Education Act to modernize education in response to the Sputnik launch with the intention of ensuring American dominance in science and technology, as many believed that the education system had “led to an insufficient proportion of our population educated in science, mathematics, and modern language and trained in technology”. One of the curricula that emerged from this reform effort has become known as “New Math”. Now a shorthand for failure in education and education reform, “New Math” aimed to teach students a more conceptual understanding of numeracy and mathematical concepts over a rote memorization of arithmetic and was based largely on set theory. Parents objected to this curriculum because they didn’t understand it and couldn’t help their children with their homework. Teachers were unhappy with the curriculum because they didn’t have the conceptional understanding and the professional learning to be adequately prepared to instruct students in these new methods at a deep level. In short, the implementation of this curriculum failed, even though the curriculum itself was theoretically solid. If all of this sounds like Common Core Math….well….

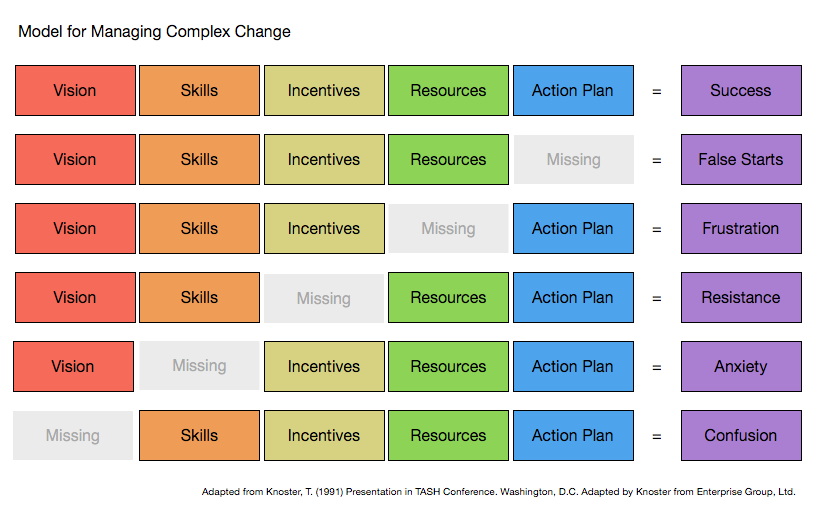

While managing change in any context is difficult, managing change in an educational context may be among the most difficult. Managing change is as much art as science, and is much more about building positive culture than about the change “being the right thing”. The best, most positive and worthwhile change will almost always fail without sufficient buy-in, a shared vision, professional learning, and adequate resources. This is represented best in Knoster’s Model for Managing Complex Change.

In any change management culture, it’s also critical to manage the different types of personalities within a school and their approach to change. The late Dr. Michael Armstrong, a former local principal, described these groups as trailblazers, pioneers, settlers, nomads, and snipers.

Design Thinking

Design “with.” Don’t design “for.”

When we are talking about “managing change”, we are really looking at how to design new solutions and new approaches for the way things are currently done in schools. Design thinking is an approach to solving complex problems that was popularized by the Stanford University Design School (d.School). Design thinking focuses on both solving complex problems and focusing on human-centered solutions. Design thinking differs from traditional design in that:

- The process focuses on finding the best solution, and is less concerned with the problem itself or the process.

- In traditional design, problems are solved for people by “experts”. In design thinking, problems are designed with people - the expertise and experience of all stakeholders is valued.

- Design thinking encourages design without constrains and boundaries, and encourages “productive struggle” and failure as a mechanism for improving and iterating on the final product.

Design thinking is often referred to as a process with five discrete stages:

- Empathize: In this stage, designers seek to understand the needs of the community being served and the audiences that will be impacted by their work.

- Define: In this stage, after learning more about the problem, designers will define the problems to be overcome and addressed to get from the “current state” to the “ideal state”.

- Ideate: In this stage, designers will develop ideas to address the problem.

- Prototype: In this stage, designers will design small-scale easy to implement models that can be used to gather data and refine the design.

- Testing: In this stage, the design is tested, evaluated, and refined.

Source: Stanford d.School

Source: Stanford d.School

In reality, these are not discrete steps, nor do you move from phase to phase and leave everything behind. For example, when you are creating your prototypes, a good designer will reach back out to the people they interviewed in the empathize stage of the process for their feedback. Like many change management processes, Design Thinking has roots in the Demming Cycle (plan, do, study, act).

Visioning

Before you can begin any significant organizational change or design project, you must first create your vision - identify where it is you want to go. It isn’t enough to say “we want to be 1:1” or “we want to have students use technology” - a vision must have a compelling why - a reason for making these changes that’s rooted in the needs and wants of all of the stakeholders involved in the process. Oftentimes visioning is restricted to a small subset of “experts” - their voices and concerns are the only ones heard and identified. The vision that is created does not meet the needs of all of the students or the entire community, but rather a subset of the community which is typically whiter and wealthier than the community at large. For a great example of this reality in action, I recommend the podcast Nice White Parents.

In many ways, it’s also insufficient to say that “students are already using technology outside of school” as well - while most students do have access to technology at home, not all of them do. Additionally, the College of Education library routinely surveys their incoming freshmen - most of them consider themselves “digital immigrants”, meaning they feel they’re new to technology. While this is counterintuitive to many of us who are older, the iPad was only invented in 2010, and 4G LTE Internet has only been mainstream since 2012 - when college freshmen were in middle school. Also, it doesn’t take much time in the classroom to realize that while students are comfortable around technology, they may not know how to use it for the productive means that we intend for them. Increasingly, kindergartners have never used a mouse or physical keyboard or a non-touch display until they get to school. There are also significant disparities in the use of technology along racial and economic lines.

The vision should be responsive to the needs of the students and the local community - a student in rural Northeastern North Carolina needs Driver’s Education more than a student in New York City which may not even offer it. This is one of the key concepts behind design thinking - all solutions are representative of the culture and context in which they sit. There are no “silver bullets”, because a thing that works in school A will not work in school B because schools A and B are very different places.

The vision for a school’s digital-age learning program should be reflective of the needs of the school, the students in the school, and the local community. This will mean different things in different places. But every stakeholder should be able to see their role in realizing the vision and how they will be impacted by the changes. Consider this example from Talladega County, Alabama. While they talk about the role of technology, you can also see how they are shifting instruction accordingly, such as project-based learning. Also pay attention to the statements from the superintendent of Alabama schools about how they went about engaging in this process.

The vision is more than a statement. While it’s important to create a “vision statement”, that is a short and succinct version of the vision. The real vision for a digital-age learning vision may be several pages long. Everyone should be able to buy into the vision and be able to see themselves reflected in it. The vision statement is a good tool for stakeholders to articulate the vision for digital-age learning. There are numerous tools that should be employed to create the vision, including focus groups and surveys.

Shared Leadership

In many organizations, leadership is top-down - the leader makes all of the decisions and expects the staff to execute. While the leader may seek input on issues from employees, the leader ultimately is the one who makes the decisions.

In a shared leadership model, the leader recognizes the value in the human capacity in the organization to inform, make, and execute decisions. Shared leadership is not delegation - the leader doesn’t simply divvy up tasks and make different people responsible for them. Nor is it necessarily leadership by committee - shared leadership is a culture of governance and decision making where every stakeholder has a seat at the table and opportunities to contribute. A shared leadership culture leverages the strengths, connections, and energy of the leadership team and can usually produce a product with more buy-in than one person could alone. Shared leadership is about a culture of empowerment and relationships - the people who are leading the charge are empowered to make decisions and have respect for each other, and a mutual respect for the stakeholders in the school. Shared leadership is also both change-oriented and task-oriented. Like the visioning process, shared leadership should amplify the voices of those on the margins to ensure that their needs are met.

Often, in technology, shared leadership will take the form of a Media and Technology Advisory Committee in a school. However, as we’re seeing, moving to digital-age learning is a whole-school transformation, and keeping technology separate can prove ineffective. Once the expectation of a whole-school transformation is set, subgroups may emerge for efficiency and to leverage expertise.

A shared leadership committee should include stakeholders from across the school - teachers, support staff, parents, and students. Also, the tendency for these types of committees is to pick the “high-flyers” and the “trailblazers” for these types of groups - a truly effective shared leadership structure is reflective of the entire community it serves.

Review the video below from Wisconsin. Notice shared leadership in action - the teachers involved have a voice in developing the program as do the students, and everything from the curriculum to the furniture supports the vision.